Extraction

Synopsis

Strategies to extract facts from software systems.

Description

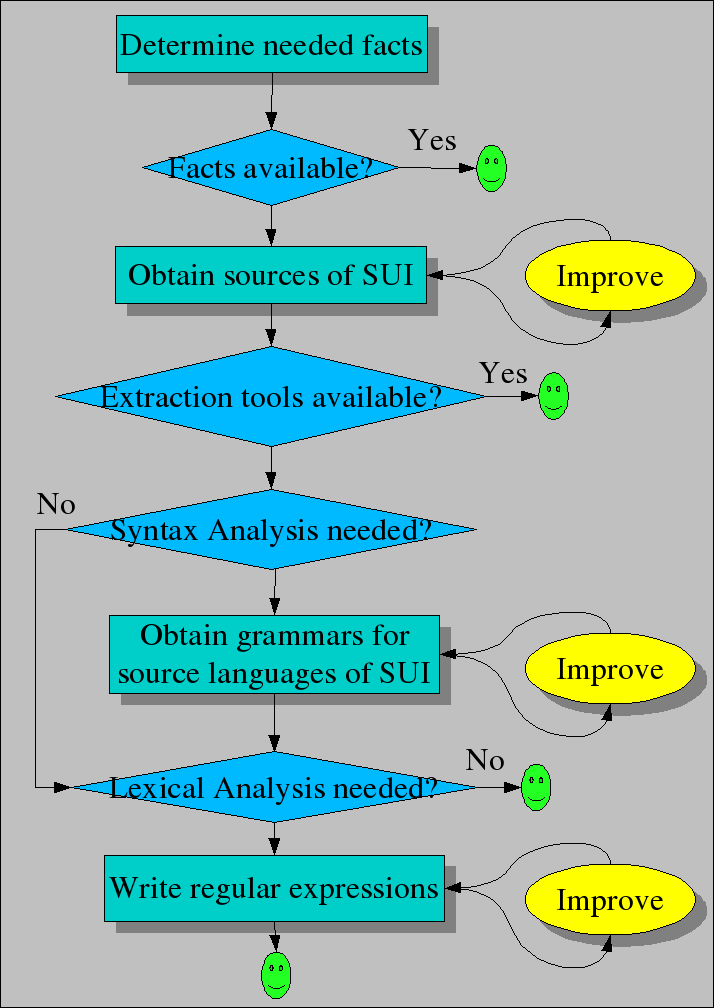

How can we extract facts from the System under Investigation (SUI) that we are interested in? The extraction workflow is shown in the figure above and consists of the following steps:

- First and foremost we have to determine which facts we need. This sounds trivial, but it is not. The problem is that we have to anticipate which facts will be needed in the next---not yet defined---analysis phase. A common approach is to use look-ahead and to sketch the queries that are likely to be used in the analysis phase and to determine which facts are needed for them. Start with extracting these facts and refine the extraction phase when the analysis phase is completely defined.

If relevant facts are already available (and they are reliable!) then we are done. This may happen when you are working on a system that has already been analyzed by others.

Otherwise you need the source code of the SUI. This requires:

Checking that all sources are available (and can be compiled by the host system on which they are usually compiled and executed). Due to missing or unreliable configuration management on the original system this may be a labour-intensive step that requires many iterations.

Determining in which languages the sources are written. In larger systems it is common that three or more different languages are being used.

If there are reliable third-party extraction tools available for this language mix, then we only have to apply them and we are done. Here again, validation is needed that the extracted facts are as expected.

The extraction may require syntax analysis. This is the case when more structural properties of the source code are needed such as the flow-of-control, nesting of declarations, and the like. There two approaches here:

Use a third-party parser, convert the source code to parse trees and do the further processing of these parse trees in Rascal. The advantage is that the parser can be re-used, the disadvantage is that data conversion is needed to adapt the generated parse tree to Rascal. Validate that the parser indeed accepts the language the SUI is written in, since you will not be the first who has been bitten by the language dialect monster when it turns out that the SUI uses a local variant that slightly deviates from a mainstream language.

Use an existing syntax definition of the source language or write your own definition. Be aware, however, that writing a grammar for a non-trivial language is a major undertaking and may require weeks to month of work. Whatever approach you choose, validate that the resulting grammar is compliant with the original grammar of the source language.

The extraction phase may only require lexical analysis. This happens when more superficial, textual, facts have to be extracted like procedure calls, counts of certain statements and the like. Use Rascal's full regular expression facilities to do the lexical analysis.

It may happen that the facts extracted from the source code are wrong. Typical error classes are:

Extracted facts are wrong: the extracted facts incorrectly state that procedure P calls procedure Q but this is contradicted by a source code inspection. This may happen when the fact extractor uses a conservative approximation when precise information is not statically available. In the language C, when procedure P performs an indirect call via a pointer variable, the approximation may be that P calls all procedures in the procedures.

Extracted facts are incomplete: the inheritance between certain classes in Java code is missing.

The strategy to validate extracted facts differ per case but here are three strategies:

Post process the extracted facts (using Rascal, of course) to obtain trivial facts about the source code such as total lines of source code and number of procedures, classes, interfaces and the like. Next validate these trivial facts with tools like wc (word and line count), grep (regular expression matching) and others.

Do a manual fact extraction on a small subset of the code and compare this with the automatically extracted facts.

Use another tool on the same source and compare results whenever possible. A typical example is a comparison of a call relation extracted with different tools.

The Rascal features that are most frequently used for extraction are:

Regular expression patterns to extract textual facts from source code.

Syntax definitions and concrete patterns to match syntactic structures in source code.

Pattern matching (used in many Rascal statements).

Visits to traverse syntax trees and to locally extract information.

The repertoire of built-in datatypes (like lists, maps, sets and relations) to represent the extracted facts.