module Type

Rascal's type system, implemented in Rascal itself.

Usage

import Type;

The goal of this module is to provide:

- reflection capabilities that are useful for deserialization and validation of data, and

- to provide the basic building blocks for syntax trees (see Parse Tree),

- provide the implementations of Rascal's type lattice: Subtype, Glb, Lub and Intersects for reified type Symbols

The following definition is built into Rascal:

data type[&T] = type(Symbol symbol, map[Symbol, Production] definitions);

For values of type type[...] the static and dynamic type systems satisfy three additional constraints over the rules of type-parameterized data types:

- For any type

T:#Thas typetype[T] - For any type T and any value of

type[T], namelytype(S, D)it holds that S is the symbolic representation of typeTusing the Symbol type, and - ...

Dholds all the necessary data and syntax rules required to form values of typeT.

In other words, the # operator will always produce a value of type[&T], where &T is bound to the type that was reified and said value will contain the full grammatical definition for what was bound to &T.

The Subtype relation of Rascal has all the mathematical properties of a finite lattice; where Lub implements the join and Glb implements the meet operation. This is a core design principle of Rascal with the following benefits:

- Type inference has a guaranteed least or greatest solution, always. This means that constraints are always solvable in an unambigous manner.

- A principal type can always be computed, which is a most precise and unique solution of a type inference problem. Without the lattice, solution candidates could become incomparable and thus ambiguous. Without this principal type property, type inference is predictable for programmers.

- Solving type inference constraints can be implemented efficiently. The algorithm, based on Lub and Glb, makes progress deterministically and does not require backtracking to find better solutions. Since the lattice is not very deep, fixed-point solutions are always found quickly.

Much of the aspects of the Subtype lattice are derived from the fact that Rascal's values are immutable or readonly. This typically allows for containers

to be co-variant in their type parameters: list[int] <: list[value]. Because all values in Rascal are immutable, and implemented using persistent data-structures,

its type literals do not feature annotations for co- and contra-variance. We can assume co-variance practically everywhere (even for function parameters).

Function types in Rascal are special because functions are always openly extensible, as are the modules they are contained in. This means that the parameter types of functions can also be extended, and thus they are co-variant (accepting more rather than fewer kinds of data). Contra-variance is still also allowed, of course, and so we say function parameter types are "variant" in both directions. Lub has been hard-wired to choose the more general (co-variant) solutions for function parameter types to reflect the general applicability of the openly extensible functions.

Examples

rascal>import Type;

ok

rascal>#int

type[int]: type(

int(),

())

rascal>#rel[int,int]

type[rel[int,int]]: type(

set(tuple([

int(),

int()

])),

())

rascal>data B = t();

ok

rascal>#B

type[B]: type(

adt(

"B",

[]),

(adt(

"B",

[]):choice(

adt(

"B",

[]),

{cons(

label(

"t",

adt(

"B",

[])),

[],

[],

{})})))

rascal>syntax A = "a";

ok

rascal>#A;

type[A]: type(

sort("A"),

(

layouts("$default$"):choice(

layouts("$default$"),

{prod(

layouts("$default$"),

[],

{})}),

empty():choice(

empty(),

{prod(

empty(),

[],

{})}),

sort("A"):choice(

sort("A"),

{prod(

sort("A"),

[lit("a")],

{})})

))

rascal>type(\int(),())

type[value]: type(

int(),

())

data Symbol

A Symbol represents a Rascal Type.

data Symbol

= \int()

| \bool()

| \real()

| \rat()

| \str()

| \num()

| \node()

| \void()

| \value()

| \loc()

| \datetime()

;

Symbols are values that represent Rascal's types. These are the atomic types. We define here:

- ❶ Atomic types.

- ❷ Labels that are used to give names to symbols, such as field names, constructor names, etc.

- ❸ Composite types.

- ❹ Parameters that represent a type variable.

In Parse Tree, see Symbol, Symbols will be further extended with the symbols that may occur in a parse tree.

data Symbol

data Symbol

= \label(str name, Symbol symbol)

;

data Symbol

data Symbol

= \set(Symbol symbol)

| \tuple(list[Symbol] symbols)

| \list(Symbol symbol)

| \map(Symbol from, Symbol to)

| \adt(str name, list[Symbol] parameters)

| \cons(Symbol \adt, str name, list[Symbol] parameters)

| \alias(str name, list[Symbol] parameters, Symbol aliased)

| \func(Symbol ret, list[Symbol] parameters, list[Symbol] kwTypes)

| \reified(Symbol symbol)

;

data Symbol

data Symbol

= \parameter(str name, Symbol bound)

;

function \rel

rel types are syntactic sugar for sets of tuples.

Symbol \rel(list[Symbol] symbols)

function \lrel

lrel types are syntactic sugar for lists of tuples.

Symbol \lrel(list[Symbol] symbols)

function overloaded

Overloaded/union types are always reduced to the least upperbound of their constituents.

Symbol overloaded(set[Symbol] alternatives)

This semantics of overloading in the type system is essential to make sure it remains a lattice.

data Production

A production in a grammar or constructor in a data type.

data Production

= \cons(Symbol def, list[Symbol] symbols, list[Symbol] kwTypes, set[Attr] attributes)

| \choice(Symbol def, set[Production] alternatives)

| \composition(Production lhs, Production rhs)

;

Productions represent abstract (recursive) definitions of abstract data type constructors and functions:

cons: a constructor for an abstract data type.func: a function.choice: the choice between various alternatives.composition: composition of two productions.

In ParseTree, see Production, Productions will be further extended and will be used to represent productions in syntax rules.

data Attr

Attributes register additional semantics annotations of a definition.

data Attr

= \tag(value \tag)

;

function \var-func

Transform a function with varargs (...) to a normal function with a list argument.

Symbol \var-func(Symbol ret, list[Symbol] parameters, Symbol varArg)

function choice

Normalize the choice between alternative productions.

Production choice(Symbol s, set[Production] choices)

The following normalization rules canonicalize grammars to prevent arbitrary case distinctions later Nested choice is flattened.

The below code replaces the following code for performance reasons in compiled code:

Production choice(Symbol s, {*Production a, choice(Symbol t, set[Production] b)})

= choice(s, a+b);

function subtype

Subtype is the core implementation of Rascal's type lattice.

bool subtype(type[&T] t, type[&U] u)

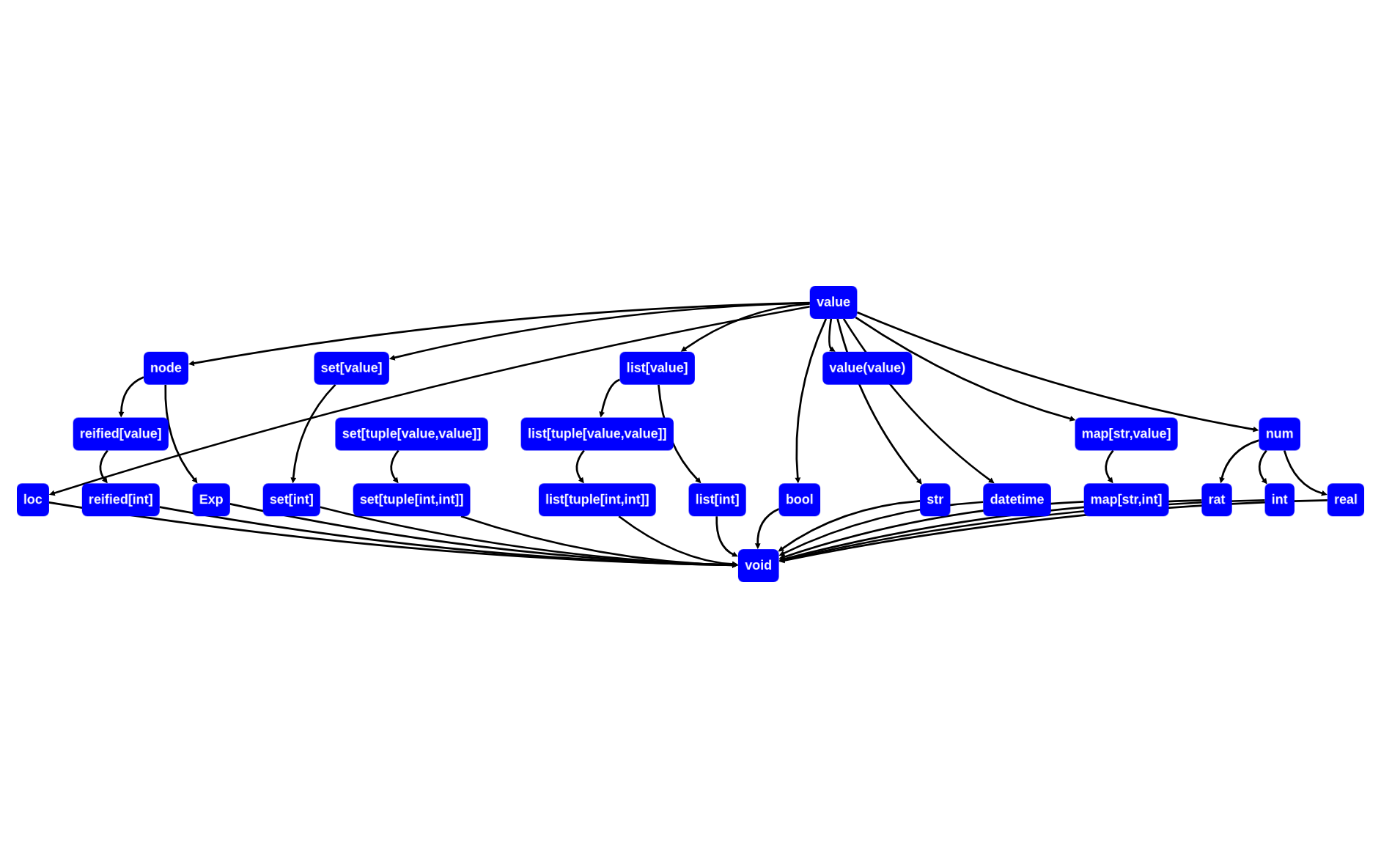

The following graph depicts Rascal's type lattice for a number of example types, including:

- all the builtin types, with

valueas maximum andvoidas the minimum of the lattice - parameterized container types (co-variant)

- a function type example (variant in parameter positions, both directions)

- a data type

Exp - a reified type

type[value]andtype[int](co-variant)

Examples

rascal>import Type;

ok

rascal>subtype(#int, #value)

bool: true

rascal>subtype(#value, #int)

bool: false

function subtype

This function documents and implements the subtype relation of Rascal's type system.

bool subtype(Symbol s, Symbol t)

function intersects

Checks if two types have a non-empty intersection, meaning there exists values which types with both as a supertype

bool intersects(Symbol s, Symbol t)

bool intersects(type[&T] t, type[&U] u)

Consider tuple[int, value] and tuple[value, int] which are not subtypes of one another,

but all the values in their intersection, tuple[int, int] belong to both types.

Type intersection is important for the type-checking of pattern matching, and since function parameters are patterns in Rascal, also for the type-checking of function parameters. Pattern matching between two types is possible as long as the intersection is non-empty. This is true if one is a sub-type of other, or vice verse: then the intersection is the subtype. However, the above tuple example also shows there can be non-empty intersections when the types are not sub-types.

function comparable

Check if two types are comparable, i.e., one is a subtype of the other or vice versa.

bool comparable(Symbol s, Symbol t)

bool comparable(type[value] s, type[value] t)

function equivalent

Check if two types are equivalent, i.e. they are both subtypes of each other.

bool equivalent(Symbol s, Symbol t)

bool equivalent(type[value] s, type[value] t)

function eq

Strict structural equality between values.

bool eq(value x, value y)

The difference between eq and == is that no implicit coercions are done between values of incomparable types

at the top-level.

The == operator, for convience, equates 1.0 with 1 but not [1] with [1.0], which can be annoying

when writing consistent specifications. The new number system that is coming up will not have these issues.

Examples

rascal>import Type;

ok

rascal>1 == 1.0

bool: true

rascal>eq(1,1.0)

bool: false

function lub

The least-upperbound (lub) of two types is the common ancestor in the type lattice that is lowest.

Symbol lub(Symbol s1, Symbol s2)

type[value] lub(type[&T] t, type[&T] u)

This function implements the lub operation in Rascal's type system, via unreifying the Symbol values and calling into the underlying run-time Type implementation.

Examples

rascal>import Type;

ok

rascal>lub(#tuple[int,value], #tuple[value, int])

type[value]: type(

tuple([

value(),

value()

]),

())

rascal>lub(#int, #real)

type[value]: type(

num(),

())

function glb

The greatest lower bound (glb) between two types, i.e. a common descendant of two types in the lattice which is largest.

Symbol glb(Symbol s1, Symbol s2)

type[value] glb(type[&T] t, type[&T] u)

This function implements the glb operation in Rascal's type system, via unreifying the Symbol values and calling into the underlying run-time Type implementation.

Examples

rascal>import Type;

ok

rascal>glb(#tuple[int,value], #tuple[value, int])

type[value]: type(

tuple([

int(),

int()

]),

())

rascal>glb(#int, #real)

type[value]: type(

void(),

())

data Exception

data Exception

= typeCastException(Symbol from, type[value] to)

;

function typeCast

&T typeCast(type[&T] typ, value v)

function make

Dynamically instantiate an data constructor of a given type with the given children and optional keyword arguments.

&T make(type[&T] typ, str name, list[value] args)

&T make(type[&T] typ, str name, list[value] args, map[str,value] keywordArgs)

This function will build a constructor if the definition exists and the parameters fit its description, or throw an exception otherwise.

This function can be used to validate external data sources against a data type such as XML, JSON and YAML documents.

function typeOf

Returns the dynamic type of a value as a ((Type-Symbol)).

Symbol typeOf(value v)

As opposed to the # operator, which produces the type of a value statically, this function produces the dynamic type of a value, represented by a symbol.

Examples

rascal>import Type;

ok

rascal>value x = 1;

value: 1

rascal>typeOf(x)

Symbol: int()

Benefits

- constructing a reified type from a dynamic type is possible:

rascal>type(typeOf(x), ())

type[value]: type(

int(),

())

Pitfalls

Note that the typeOf function does not produce definitions, like the

reify operator # does, since values may escape the scope in which they've been constructed.